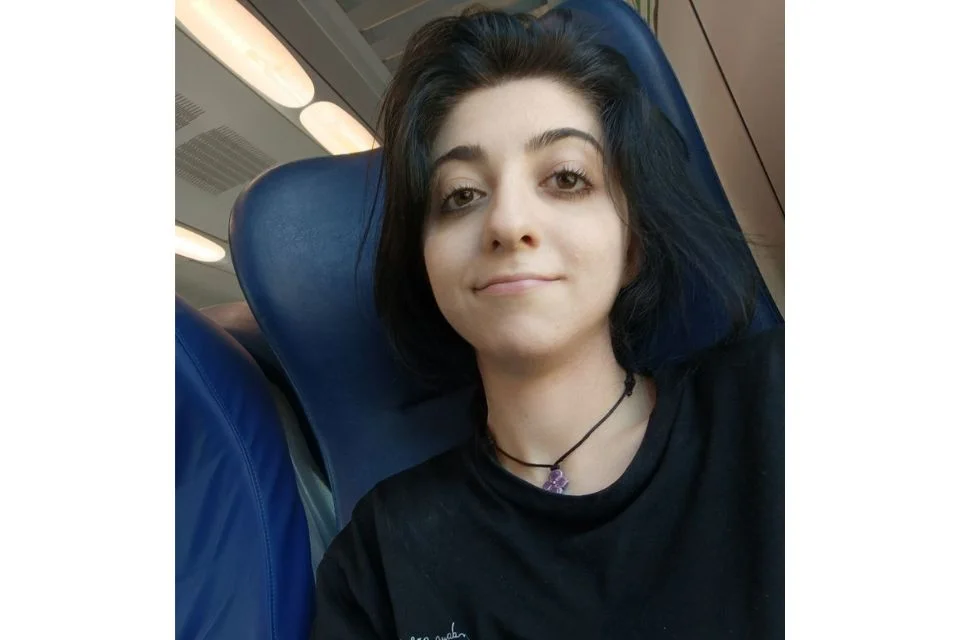

5 Tips on Writing: With Anastasia Rizzo

Hello!

I’m Anastasia, narrative designer and writer. I’m 27 years old, the first game I fell in love with is Claw and I became a grammar nerd at around the age of 8 thanks to the rigid syntax on Magic:The Gathering cards (true story). I started crafting stories before being able to actually write one. My tales were mainly about imaginary dead relatives, a wolf pack my grandma owned (in Sicily, so my friends couldn’t claim I was a fraud), and epic fights with invisible monsters. Then I grew up to become more and more boring, and the only way to save myself was to turn my passion for stories into a way to pay the bills (we’re still working on that).

I got my degree in Modern Literature, then a Master in Playwriting and Dramaturgy. From dramaturgy to narrative design, the journey is easier and smoother than one could immediately guess. I know, right? I was surprised too. I’m currently the narrative designer at Runaways Studio, and we’ve been developing our first game, a narrative-driven FPS called Imperfection.

In the meantime, I study, practice and teach writing and narrative design: study, because one should never stop learning and I’m just at the beginning of my adventure, practice since you’re not crafting anything otherwise, teach as that’s what I do at AIV (Italian Videogames Academy) 🙂 I hope my tips on writing and narrative design can bring you some useful perspectives 😀 Thank you for reading this, and in case you want to have a chat with me, feel free to drop a message on LinkedIn!

Hooking Your Audience

A player will want to feel the weight and power of responsibility. Make the story part of the gameplay in any way possible: a minigame to translate an ancient message and unlock a reward connected to a storyline, a skill tree that reflects the personality of the character and the other way around (especially if players took part to any change in that), and so on. Writing can be the game content’s meat, but engraving it in the overall experience will make the story captivating. “Hey, but this is not about writing!” Nope, it’s about design, but if you don’t consider that in your game writing, what are you doing?

Extra tip: give the highest value to your voice actors (if you have them). Do not underestimate their insight and analytical skills: they give soul, authenticity and intensity to your words and may be the difference between an engaged and hyped player and a bored and detached one, especially if you have cutscenes and long dialogues!

The reader will see plot holes or get annoyed by empty characters, to the point of feeling robbed of their time as they trust the author with it. So make sure you challenge their explorative souls with pieces of information from one chapter to the other, just like weaving threads (even symbols, sensations and emotions: you only have your words to build that world). Having that implied question will intrigue the reader’s mind and urge them to see if their theories are right,

especially when every element of the plot is given its rightful credit and you’re avoiding cliches. If I feel like I already know it all, I won’t need to read further.

Extra tip: from reader to writer first of all, give titles to your chapters. Numbers lack personality, differently from tricky titles revealing inner thoughts or other implications, which add a new layer to the storytelling.

A viewer will see your writing more than reading it. Use actions, characters and environment in place of wordy, explicit lines for a repeated theme.

The actions in the scripts, as parentheticals, are amazing tools for that. This will make the viewer feel like the story is evolving and aware of itself, adding nuances while being consistent, giving the sacred space to animations and performance, your best friends and means for a great show-don’t-tell. E.g.: we have a character grieving, which is a big deal. It’s also a complex set of emotions that shouldn’t end in one dramatic scene: new small habits defining the character’s change will raise the curiosity of the viewer.

Extra tip: also actors, just like before!

The bottom line is: we search for movement in any story. An e-motion is never “static”. If one can foresee every aspect of the story or one’s efforts in understanding it are annihilated by under-developed storylines, that thrill will be looked for elsewhere. Every (lean-back or lean-forward) medium creates a certain pattern in the way we communicate that movement to our audience. And that audience will be hooked, once they feel rewarded as much as challenged in the context of that medium.

Mastering Plot Development

Most of the time we focus on the major events we want in our story, but if the audience cannot relate those to the characters’ or that world’s authentic reactions and potential domino effect, we might miss some logical expectations and possible twists.

Start from and keep your mind on the characters (or anything acting as such) and the way everything acts and reacts.

Not just the protagonist or the villain: give the secondary characters valid reasons for their existence, and make them react to what happens accordingly.

E.g. What about that old woman that was saved by the hero at the beginning of the story (as part of the tutorial, for instance)? What if she was a disgraced aristocrat from the opposite faction that, thanks to the hero’s actions, unexpectedly supported them revealing her identity much later?

Or maybe something terrible happened to a group of people and there are survivals to the catastrophe: the audience would expect some of them to want revenge or take sides, even if we as writers needed that event for another thing entirely and didn’t think about those people (rather “pawns”) that much. Alternatively, an event might be so catastrophic, the whole region has been affected: the audience would want to see those effects on the story, even if it’s not the core of it.

Effective World-Building Strategies

Small details will make your world pulse with liveness, especially if the former are logically implied in that society/world’s features.

For instance,

- a highly competitive society may have a certain way to carry their values in their language and speech. “Winning” and “losing” may be expressed in many ways as central elements of life. Their language (in a broad sense) will probably be more focused on quantifiable measurements and zero-sum conditions.

- A way a dragon communicates with their body may suggest how much they’re accustomed to humanoids. Maybe there’s an anecdote of a misunderstanding between dragons as one was raised with humans and the other has never seen one. For instance, the latter may feel threatened by a simple gesture like nodding, while the former may use it to agree with their interlocutor.

Both the examples nurture the audience’s imagination, not just ours.

Extra tip: do a lot of research, for instance in history, (any specific branch of) science and speculative fiction. The first will surprise you with incredible events and traditions, some insight on how certain groups can be understood and therefore re-built in a fictional world; the second allows you to understand the miracles of nature, so close to the needs of society; the third is the work of those who elaborated all that content before you, with their own problems, conflicts and solutions.

Techniques for Character Development

External and inner conflicts build on the natural contradictions of a round character (that one that actually “develops”).

If you create contrasting roles and traits in the same character, giving both sides value, the development will naturally evolve those dynamics. A villain that suffered from a terrible childhood may destroy villages in a blink of an eye, but abruptly stop in front of a child with similar traumas. What would happen if that scene not only gave the writer the excuse to slow the villain down before the hero can arrive and save the day?

What if saving that kid brought a new nuance to light, without adding anything new to the lore or the cast? Characters as live “people”, almost ready to face their worlds without their creator’s careful guidance, are those that have rich possibilities to develop.

Extra tip: start from their fears. If you prefer, you can have two or three different fears depending on how deep and conscious those are. Relate them to a theme the character carries (“Our past never leaves us”, “Family is all that matters”, “Fighting for your freedom always brings sacrifices”). How does the character and their fears relate to their theme throughout their development? Is there any change at all?

Crafting Meaningful Decisions

Meaningful choices are a consequence of everything that was told before, from the players’ and characters’ perspective: give their wishes and perceptions the highest value. Some choices may be challenging for us writers, but consistent with that character and therefore appreciated by the audience.

Honestly, I’m not always great at this; it’s so hard to put the perception of the story before the events unravelling in our minds. I believe (extra tip here) being a dungeon master in our spare time can help us writers understand the process: players don’t care about what we imagine the story to become, but rather about the connection between their understanding of it and their characters.

What are your strengths in writing and narrative design?

I love connecting elements of the plot, seeking and giving value to patterns in the narrative. My writing is very keen towards dark and dramatic scenes, deep inner worlds and symbolic storytelling. I write both prose and poetry, which allows me great flexibility in terms of style.

Moreover, being trained in different media (mainly theatre and literature, apart from game design which I’ve been studying through trial-and-error) is such a great way to avoid getting stuck in “one big box” kind-of-mindset. This is very helpful when working in small teams and bringing different perspectives to the table, as narrative designers are often asked to do.

Which games or stories have you worked on?

I wrote a play, two short horror stories, a horror script and epistolary story, with more projects currently in progress. Speaking of narrative design and game writing, I have worked on

MoonXrossed Princess with Konditorei and Imperfection at Runaways Studio, plus smaller projects for game jams.

A Wish for Interactive Audio Stories

This War of Mine would make such an interesting audio interactive story in my opinion. Not only the theme and setting are so vital to tackle now, but the importance of sound, as the lack of it, would have an incredible, striking effect. I’d imagine an experience with strong similarities to the game, also highlighting flashbacks that create contrasts between past and present.

Register for our Free Writing Workshop now!

If you are interested in creating your own interactive audio story, you can apply for our free webinar! It will introduce you to our interactive story game engine, TWIST, and teach you how to use it to create interactive audio stories.

Interested in contributing to our blog series?

If you would also like to publish a blog post on our website and share your own story with interested readers, simply fill out the contact form.